Is Obesity Genetic?

Obesity tends to run in families – but it’s not just about shared genes or habits. While genetics plays a role in body weight, emerging research suggests there’s more to the story.

Through a field known as epigenetics, health experts are learning that factors like diet, stress, and environmental exposures can change how certain genes are expressed – and that these changes can sometimes be inherited.

In other words, while obesity may be hereditary, it’s not just about the DNA you’re born with. It’s also about the conditions that shape how that DNA functions, possibly even before you’re born.

What is Epigenetics?

Epigenetics refers to changes in how genes are expressed (or turned on or off) without altering the actual DNA sequence. In other words, the genetic code stays the same, but how the body reads and uses that code can shift based on outside influences.

These changes are shaped by external factors like diet, stress, physical activity, toxins, and even sleep patterns. Over time, these influences can leave a biological mark that affects how certain genes function.

Two of the most studied epigenetic mechanisms are:

DNA methylation: The addition of tiny chemical markers to your DNA that act like a dimmer switch, turning down or even turning off certain genes so they’re less active or not used at all.

Histone modifications: Changes to the proteins that help package DNA, affecting how tightly genes are wound and how easily they can be accessed for expression.

Certain environmental exposures can trigger epigenetic changes in genes that control metabolism, appetite, fat storage, and insulin sensitivity – making epigenetics and obesity an increasingly important area of research.

How Epigenetics Can Impact Weight

Your genes influence how your body processes food, stores fat, and regulates hormones like insulin. Epigenetics adds another layer to the picture. When environmental factors like poor diet, chronic stress, or chemical exposures change how certain genes are expressed, it can affect key processes involved in weight regulation.

These epigenetic changes may make it easier for the body to store fat, alter how efficiently calories are burned, or reduce sensitivity to insulin – all of which can raise the risk of developing obesity over time.

Animal and human studies have linked bad eating habits and obesity risk to these kinds of epigenetic shifts. For example, research has shown that mice fed high-fat diets before pregnancy can pass on changes in metabolism to their offspring. In humans, patterns of epigenetics and obesity have been observed in children born to parents with obesity, even when the children’s diets are different from their parents'.

To be clear, epigenetics doesn’t cause obesity on its own – but it can influence how genes related to weight are turned up or down, potentially increasing the likelihood of weight gain under certain conditions.

Get prescription weight loss medication online.

Find out if you're eligible for GLP-1s, and get started on your weight loss journey for as low as $75/month.

Can Obesity Be Passed Down?

When we think about inherited traits, we usually picture genes passed from parent to child through DNA.

Through a process called transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, a parent’s environment – even before conception – can influence how genes are expressed in their children. Factors like nutrition, stress, or exposure to toxins can leave chemical marks on sperm or egg cells – which may then affect how the next generation’s body regulates things like metabolism, appetite, and fat storage.

It’s not just about maternal health during pregnancy, either. Studies have shown that a father’s diet and overall metabolic health can also impact the developing fetus through changes in sperm. In short, both parents play a role.

So while genetics do contribute to a person’s risk of developing obesity, it’s not just about the DNA you inherit – it’s also about how your parents’ environment and lifestyle may shape the way your genes function.

The Dutch famine study

One of the most well-known examples of transgenerational epigenetic effects comes from people born during the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945. Children conceived during this famine had higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic issues later in life – despite returning to normal diets after birth. This study suggests that early nutritional stress can shape long-term health outcomes through epigenetic mechanisms.

Why This Matters for Public Health and Personal Choices

The idea that lifestyle habits can influence not only your own health but also that of future generations might sound daunting – but it’s also empowering. One of the most promising aspects of epigenetics is that many of these changes are not permanent. In fact, they may be reversible or modifiable through choices you make every day.

This growing body of research highlights opportunities for prevention – not just treatment. Healthier eating patterns, regular physical activity, stress management, and reducing exposure to environmental toxins like endocrine-disrupting chemicals could all play a role in shaping healthier outcomes for the next generation.

Importantly, this isn't about blame. Rather, it’s a chance to understand how deeply connected our environment, behavior, and biology really are.

Where Can I Learn More About Creating Healthy Habits?

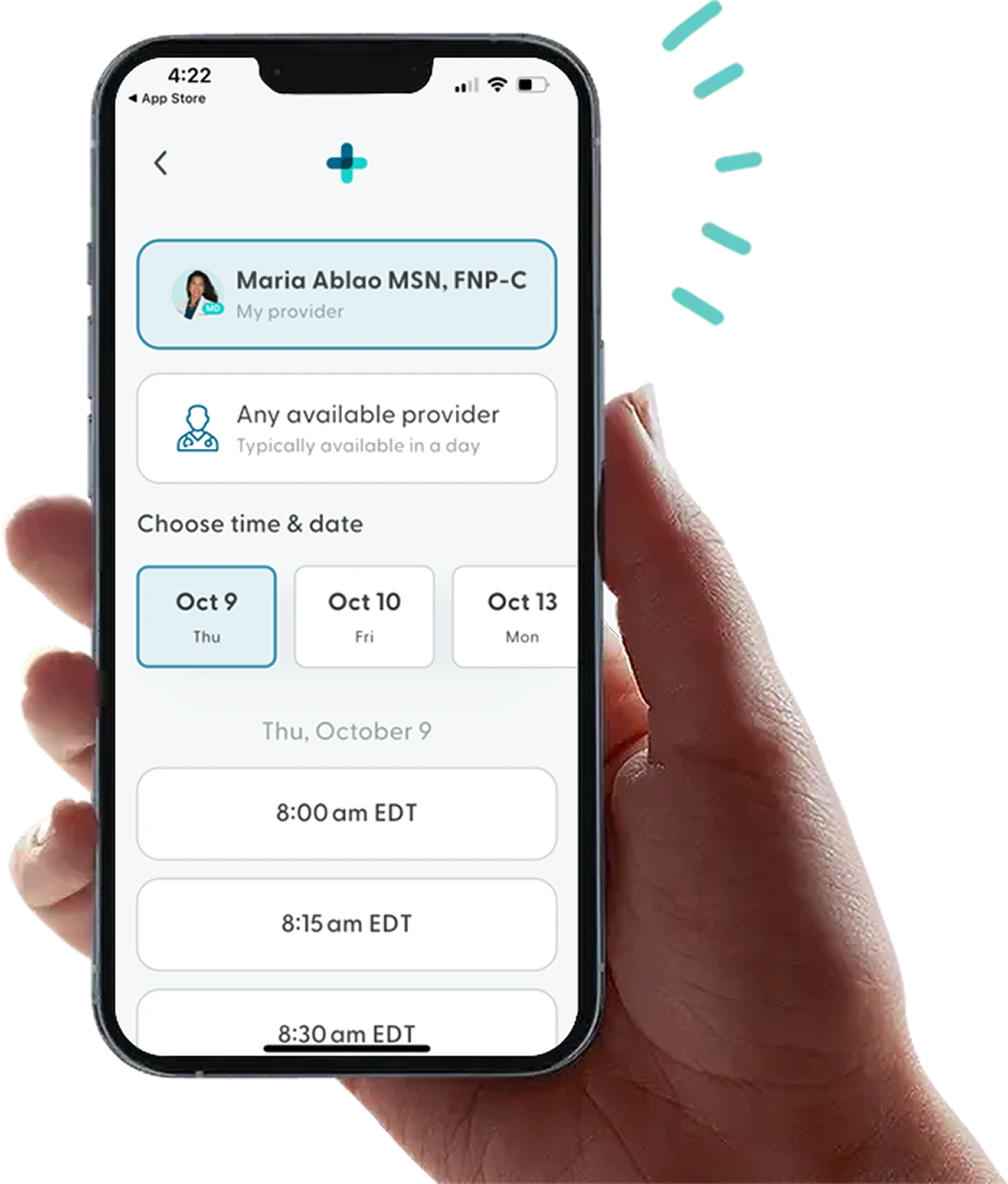

If you want to learn how to maintain a healthy diet to promote weight loss, LifeMD is here to help.

A medical professional can assist you with information about healthy metabolic strategies and weight management — all from the comfort of your own home.

You may also be interested in enrolling in the LifeMD Weight Management Program. Enrolling in the program means you’ll be working closely with licensed clinicians, and you may be prescribed a GLP-1 medication to help you lose weight.

More articles like this

Feel better with LifeMD.

Your doctor is online and ready to see you.

Join LifeMD for seamless, personalized care — combining expert medical guidance, convenient prescriptions, and 24/7 virtual access to urgent and primary care.

Medically reviewed and edited by

Medically reviewed and edited by