The Link Between Fasting and Hormone Balance

Fasting has become an increasingly popular wellness tool, and for good reason. Many people turn to fasting for weight related goals, but its influence extends far beyond the number on the scale. Fasting affects metabolic function, inflammation, cellular repair, and hormone balance. When applied thoughtfully, it can support the natural hormonal rhythms that regulate energy, mood, blood sugar, and appetite. When used too aggressively or without personalization, fasting can disrupt those same pathways. Understanding how fasting interacts with the endocrine system helps people choose an approach that supports rather than stresses the body.

Understanding How Fasting Works

Although fasting seems simple, just go without food, the physiology behind it is far more complex. An easy analogy is to picture your metabolism as a hybrid car capable of running on two fuels: glucose, your quick-access energy source, and stored fat, your long-lasting reserve. Eating keeps you operating mostly on glucose. Fasting encourages the body to switch over to stored fat, but this transition happens gradually.

Within the first four hours after eating, your body is still processing your last meal. Blood glucose rises and insulin is released.

Between four and twelve hours, insulin declines, and the body uses glycogen stored in the liver to maintain blood glucose. Around twelve hours, glycogen begins to deplete, and your body starts mobilizing more fat for fuel.

Between eighteen and thirty-six hours, most people begin producing more meaningful levels of ketones, though this timeline varies widely. Autophagy also picks up around the 12-16 hour mark, which is a natural cellular “cleanup” process where damaged proteins, old cell components, and metabolic waste are removed. Autophagy is one reason fasting is associated with longevity, improved mitochondrial function, and reduced inflammation. Deep autophagy typically requires longer fasting periods, but mild, regular stimulation may still be beneficial.

This is why popular fasting structures like 14:10 or 16:8 typically create mild fat burn but not deep ketosis.

14:10 means fasting for 14 hours and eating within a 10-hour window.

16:8 means fasting for 16 hours and eating within an 8-hour window.

Intermittent fasting patterns like these support metabolic health without reaching prolonged fasting states.

How Hormones Respond to Fasting

Insulin and glucagon: metabolic counterparts

Insulin naturally falls during fasting since there is no dietary glucose to process. This decline is one of the primary reasons fasting improves insulin sensitivity over time. Lower insulin allows the body to stop storing energy and begin breaking down stored fat.

As insulin drops, glucagon, the hormone that raises blood sugar when it becomes too low, rises in response. Glucagon helps release stored glycogen and, once glycogen is depleted, supports fat metabolism. Insulin and glucagon create a balanced system that keeps blood sugar stable.

Ghrelin: the hunger hormone

Ghrelin, commonly known as the hunger hormone, increases before meals to signal hunger. During the early stages of fasting, ghrelin may spike, creating intense hunger or cravings. However, ghrelin adapts remarkably well to routine. Once fasting becomes predictable, ghrelin levels often decrease during typical fasting hours, making fasting feel easier over time.

Leptin: long-term satiety and energy regulation

Leptin, the hormone that communicates long-term energy availability, decreases as body fat decreases. Although this can temporarily increase appetite, improved leptin sensitivity is often observed with metabolic improvements seen during fasting. Individuals with leptin resistance, common in metabolic syndrome, may particularly benefit from moderate fasting approaches.

Cortisol: stress, blood sugar, and adaptation

Cortisol plays a dual role during fasting by helping to maintain blood glucose and mobilize stored fuel. A temporary rise in cortisol during fasting is normal and part of the body’s adaptive response. Problems occur when fasting is combined with chronic stress, poor sleep, or overexercise, all of which can amplify cortisol and disrupt thyroid or reproductive hormones.

Women often experience stronger cortisol-related impacts from fasting due to the interplay between stress hormones, ovulation, and metabolic signaling.

Sex Hormones and Fasting

Fasting influences estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone in ways that can be helpful or harmful depending on a person’s physiology.

Because adipose tissue contributes to estrogen production, weight loss through fasting can help lower elevated estrogen levels, which is beneficial for individuals with estrogen dominance, insulin resistance-driven PCOS, or weight-related hormonal imbalance. However, fasting that creates too large an energy deficit or elevates stress hormones may suppress estrogen production, disrupt cycles, or impair ovulation.

Progesterone is especially sensitive to under-eating and stress. Since progesterone is only produced after ovulation, anything that interferes with ovulation, such as excessive fasting, can reduce progesterone levels, contributing to cycle irregularity, mood changes, or sleep disturbances.

Testosterone responses vary as well. Short-term fasting may increase growth hormone, supporting muscle metabolism and potentially testosterone in men. But prolonged calorie restriction can lower testosterone, especially in men with high stress or inadequate protein intake. Women with insulin-driven PCOS may see testosterone reductions as fasting improves insulin sensitivity.

Thyroid Function and Energy Availability

The thyroid responds quickly to changes in energy intake. Mild fasting windows generally do not harm thyroid function and may indirectly support it by improving insulin sensitivity. However, prolonged fasting or calorie restriction can reduce active thyroid hormone and increase reverse T3, which signals the body to conserve energy. This can cause fatigue, cold intolerance, and slowed metabolism. Individuals with thyroid disorders usually require a cautious approach.

Key Benefits of Fasting

Fasting offers several potential benefits when practiced in a balanced and sustainable way. One of the most notable is its impact on cellular repair through autophagy, a process in which the body clears damaged proteins and metabolic waste. Research suggests that autophagy increases after approximately twelve to sixteen hours without food and contributes to improved mitochondrial function, reduced inflammation, and healthier aging. Studies in both animals and humans have linked enhanced autophagy to better metabolic resilience and neurological protection, showing promise for long term health support.

Fasting is also well known for its ability to improve insulin sensitivity. Multiple clinical trials have shown that intermittent fasting can lower fasting insulin levels, support more stable blood sugar patterns, and reduce visceral fat, which collectively benefit metabolic and cardiovascular health. There is also evidence that time restricted eating improves circadian rhythm alignment, and eating within an earlier window of the day may lower glucose excursions and support healthier cholesterol profiles.

Inflammation reduction is another commonly observed benefit. Some studies show decreases in inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL 6 after consistent fasting practice, particularly when fasting is combined with nutrient dense eating patterns. Improvements in digestive function are also frequently reported. Periods without food give the gastrointestinal tract time to rest and may support motility, reduce bloating, and improve gut barrier function.

Together, these benefits illustrate why fasting has become such an appealing approach for metabolic, hormonal, and cellular support. However, the degree of benefit varies according to the duration of fasting, the timing of the eating window, the quality of the diet, and individual hormonal needs.

Morning vs. Evening Fasting: Does Timing Matter?

There are many different types of fasting. Emerging research suggests that when you fast may be just as important as how long you fast. The body’s circadian rhythm primes metabolism to be more insulin-sensitive earlier in the day. This suggests that eating earlier (and fasting later) may support metabolic health more effectively for many people.

Morning eating vs. evening fasting

Aligns with natural cortisol rhythms

Improves blood sugar regulation

Supports healthier sleep and melatonin production

Helps reduce late-night snacking, which is metabolically unfavorable

Evening eating vs. morning fasting (the most common approach)

Is often more convenient socially

Can still improve insulin sensitivity

Works well for some men

May not be ideal for women with cycle irregularities, thyroid issues, or high stress

Evening eating with morning fasting is the most common structure due to convenience. While this approach still offers benefits, individuals with hormone sensitivities such as irregular cycles, thyroid issues, or high stress may respond more favorably to earlier eating windows. Eating earlier and finishing meals earlier may support better blood sugar regulation, improved sleep, and a more aligned circadian rhythm.

When Fasting is Helpful and When it’s Not

Fasting tends to be most beneficial for individuals with:

Insulin resistance or elevated fasting insulin

Metabolic syndrome

PCOS (insulin-driven)

Inflammation or oxidative stress

Overeating patterns or nighttime eating habits

Difficulty achieving blood sugar stability

Digestive issues that improve with periods of rest

However, fasting is not ideal, or should be approached cautiously, for individuals experiencing:

High stress or HPA axis dysregulation

Hypothyroidism or Hashimoto’s

A history of eating disorders or restrictive dieting

Irregular menstrual cycles or amenorrhea

Active fertility struggles

Pregnancy or breastfeeding

Underweight or low body fat

Intense training without adequate fueling

Creating a Balanced Fasting Pattern

The most reliable approach to fasting is to begin gently. A simple twelve hour overnight fast allows individuals to observe how their body responds without overwhelming the system. Extending the fasting window gradually and only when energy, appetite, sleep, and mood remain stable helps maintain hormonal balance. Nutrient dense meals, including adequate protein, during the eating window help stabilize blood sugar and reduce stress responses. Many women benefit from adjusting fasting intensity with their menstrual cycle and choosing shorter windows during the luteal phase.

Fasting works best when viewed as a structured pause in energy intake rather than a restrictive practice. When applied thoughtfully, it supports metabolic flexibility, cellular repair, inflammation reduction, and long term hormonal stability.

Where Can You Learn More About Fasting and Hormones?

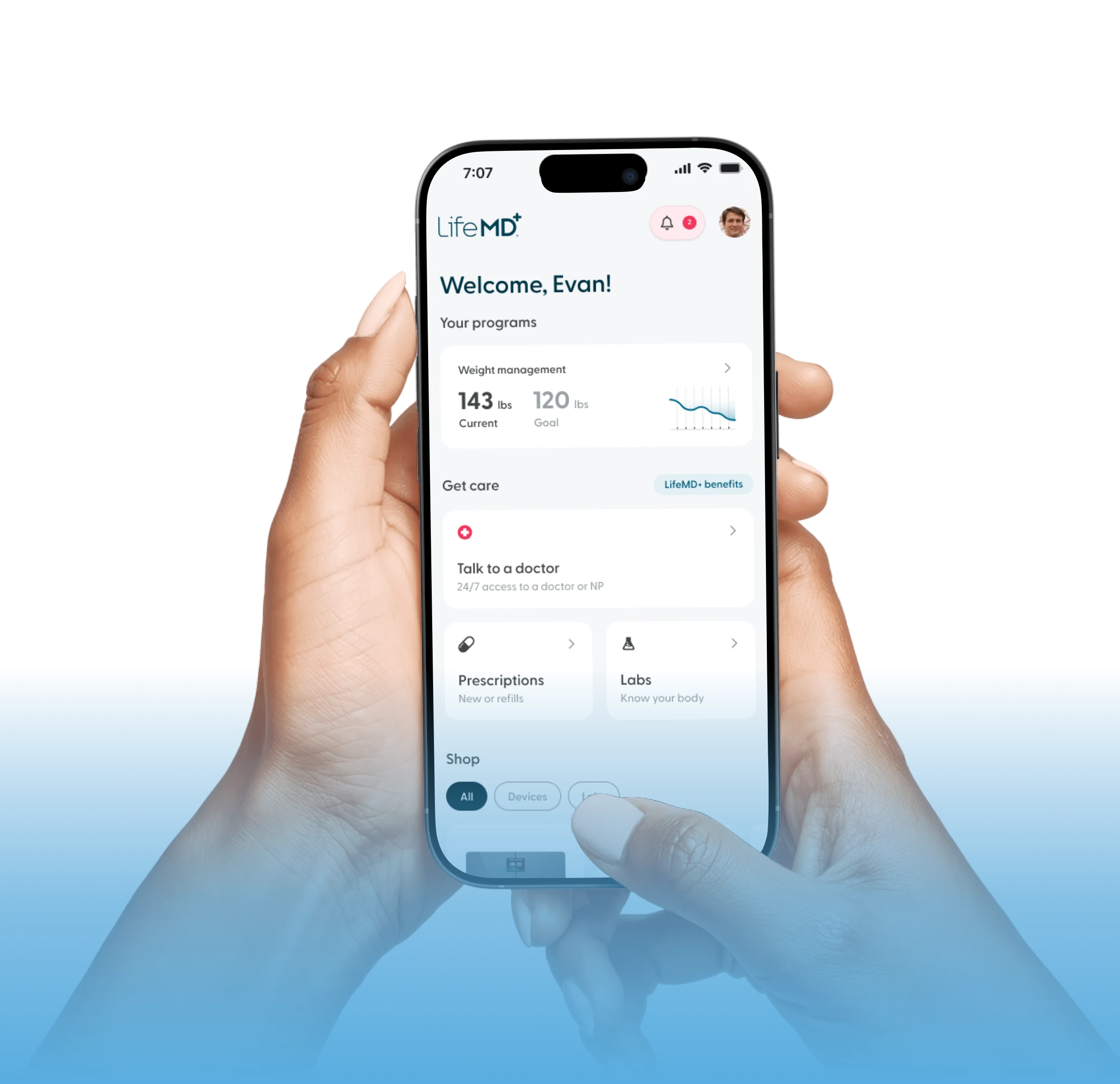

If you’re interested in fasting or concerned about how it may affect your hormonal balance, LifeMD is here to help. A team of healthcare providers can assist you with information and provide guidance on how to effectively implement fasting, or limit it depending on your goals.

Make an appointment with LifeMD to learn more about fasting, hormonal balance, and healthy ways to manage your weight.